Lec2

1. Preparation¶

The C Programming Language, by Kernighan and Ritchie (K&R)

1.1 2.9 (Bitwise operators)¶

// 1. &

101010101010101 052525

& 000000001111111 & 000177

--------------- ------

1010101 125

// 2. |

000000000 000000

| 000001010 | 000012

--------- ------

1010 12

- The precedence of the bitwise operators is not what you might expect, and explicit parentheses are often needed

1.2 5.1 (Pointers and addresses) through 5.6 (Pointer arrays)¶

- The meaning of ``adding 1 to a pointer,'' and by extension, all pointer arithmetic, is that pa+1 points to the next object, and pa+i points to the i-th object beyond pa.

- The correspondence between indexing and pointer arithmetic is very close. By definition, the value of a variable or expression of type array is the address of element zero of the array.

- In evaluating a[i], C converts it to *(a+i) immediately; the two forms are equivalent.

- When an array name is passed to a function, what is passed is the location of the initial element.

- C does not provide any operators for processing an entire string of characters as a unit.

// assigning two pointers, not copying two entire strings.

char *pmessage;

pmessage = "now is the time";

pmessage = "hello, world";

// reassign pmessage to point somewhere else, but as long as it points to the string literal, we can't modify the characters it points to.

char amessage[] = "now is the time";

char *pmessage = "now is the time";

amessage[0] = 'N';

pmessage[0] = 'N'; /* NOT WORK */

// The first function is strcpy(s,t), which copies the string t to the string s. It would be nice just to say s=t but this copies the pointer, not the characters.

void strcpy(char s[], char t[])

{

int i;

for(i = 0; t[i] != '\0'; i++)

s[i] = t[i];

s[i] = '\0';

}

void strcpy(char *s, char *t)

{

while(*t != '\0')

*s++ = *t++;

*s = '\0';

}

// any time you copy strings, using strcpy or some other method, you must be sure that the destination string is a writable array with enough space for the string you're writing.

// Remember, too, that the space you need is the number of characters in the string you're copying, plus one for the terminating '\0'.

char *p1 = "Hello, world!";

char *p2;

strcpy(p2, p1); /* WRONG */

char *p = "Hello, world!";

char a[13];

strcpy(a, p); /* WRONG */

char *p3 = "Hello, world!";

char *p4 = "A string to overwrite";

strcpy(p4, p3); /* WRONG */

1.3 6.4 (pointers to structures)¶

- never to access outside of the defined and allocated bounds of an array

- Don't assume, however, that the size of a structure is the sum of the sizes of its members.

int a[10];

int *ip;

for (ip = &a[0]; ip < &a[10]; ip++)

...

or

int a[10];

int *endp = &a[10];

int *ip;

for (ip = a; ip < endp; ip++)

...

2. Lecture 2:programming xv6 in C¶

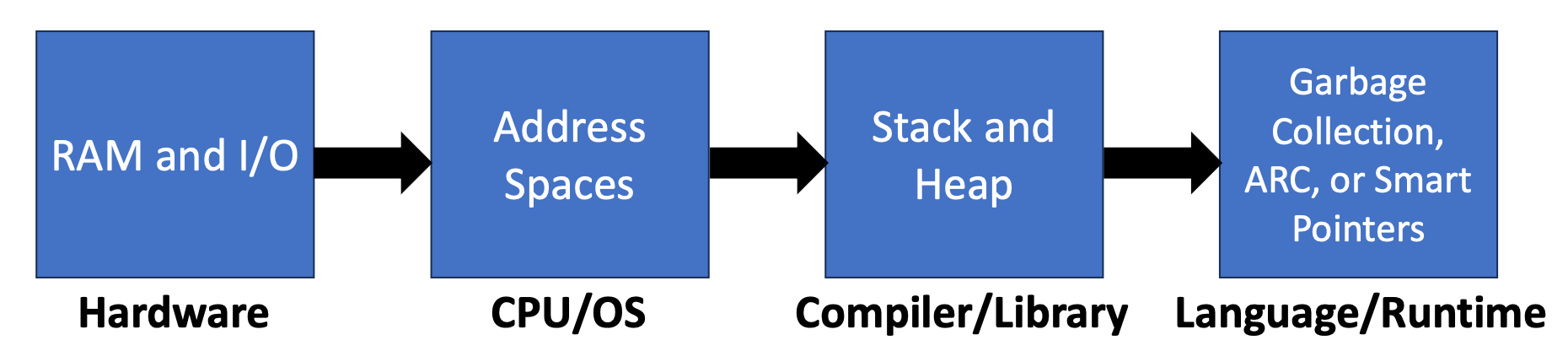

2.1 memory¶

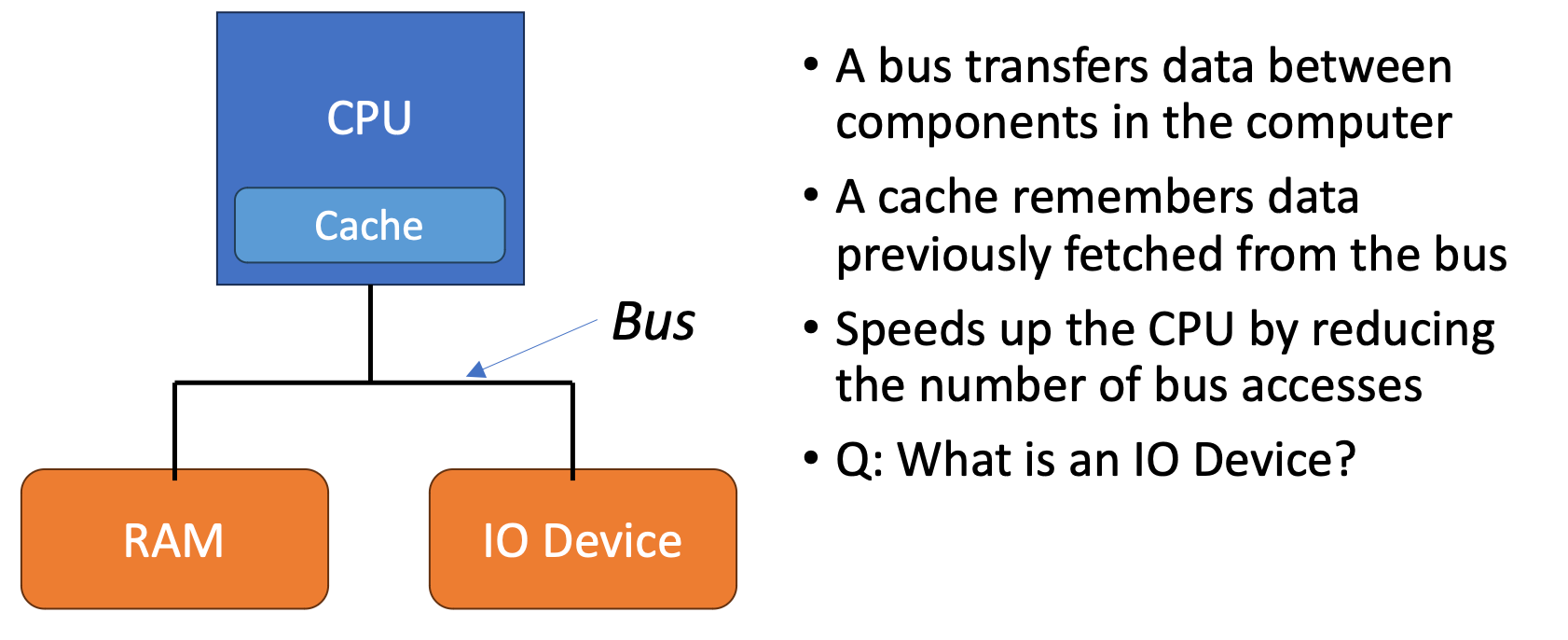

2.1.1 Hardware layer: RAM and I/O¶

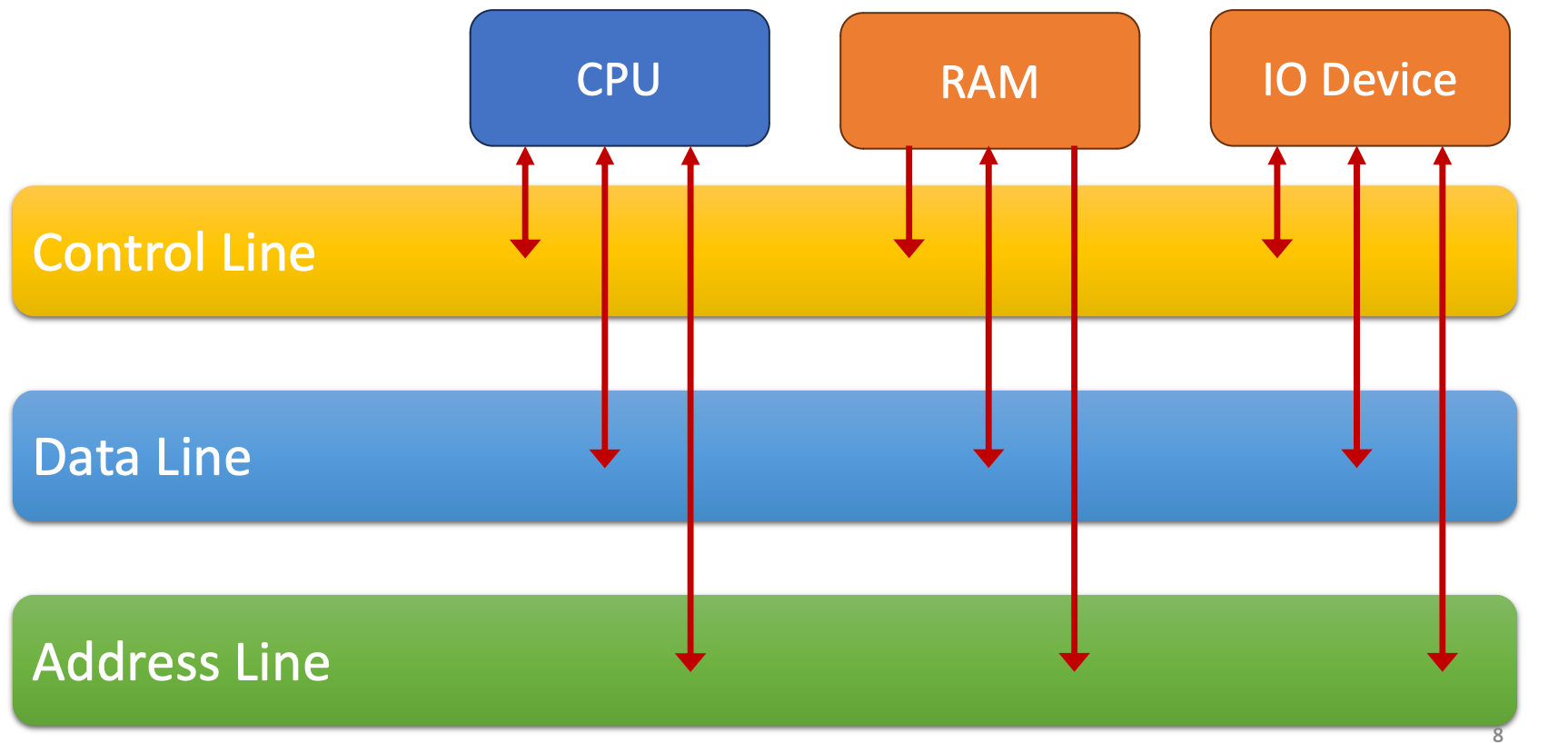

- "How does a bus work?"

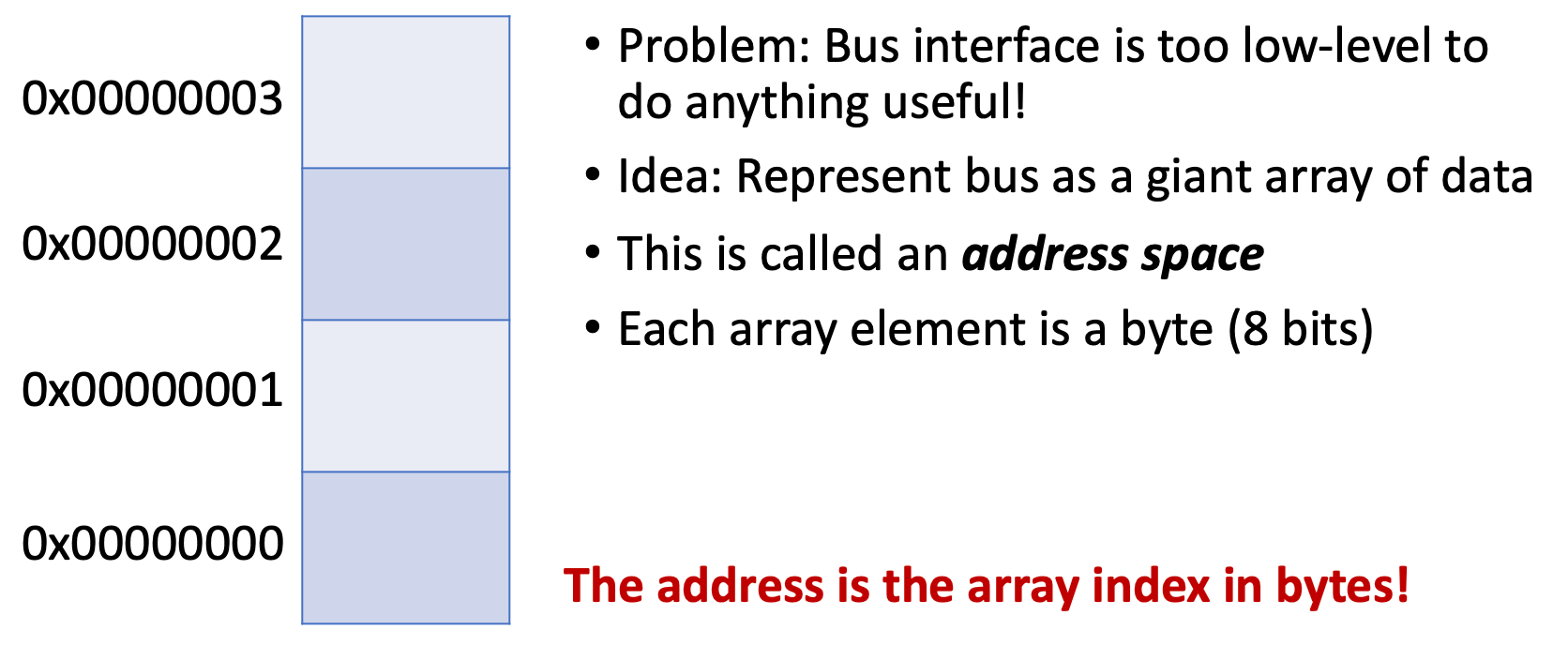

2.1.2 CPU/OS layer: Address Spaces¶

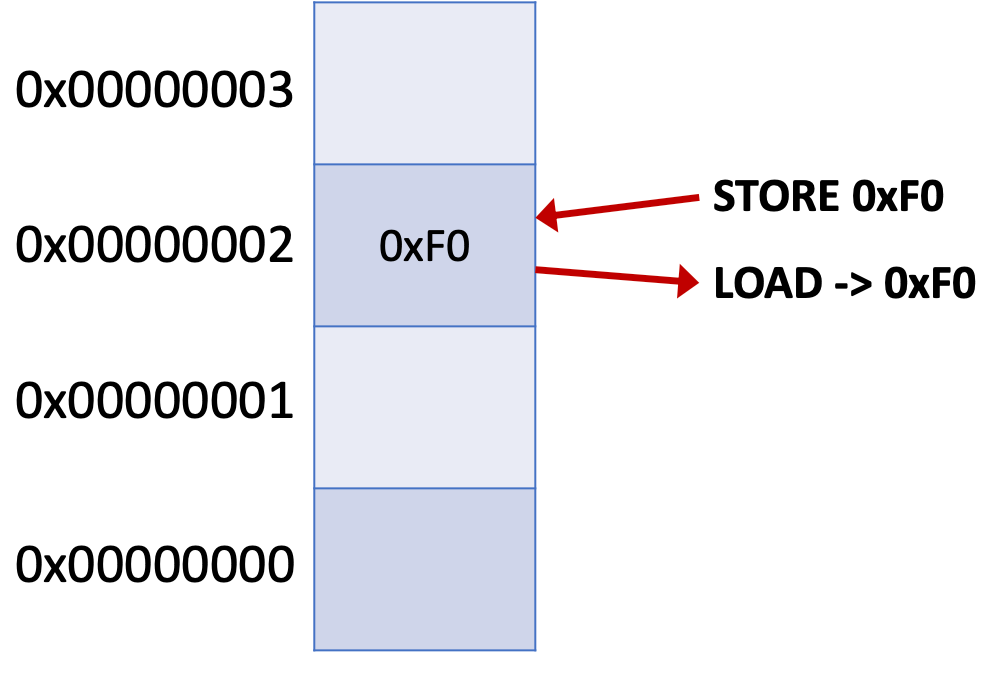

- How to interact with an address space?

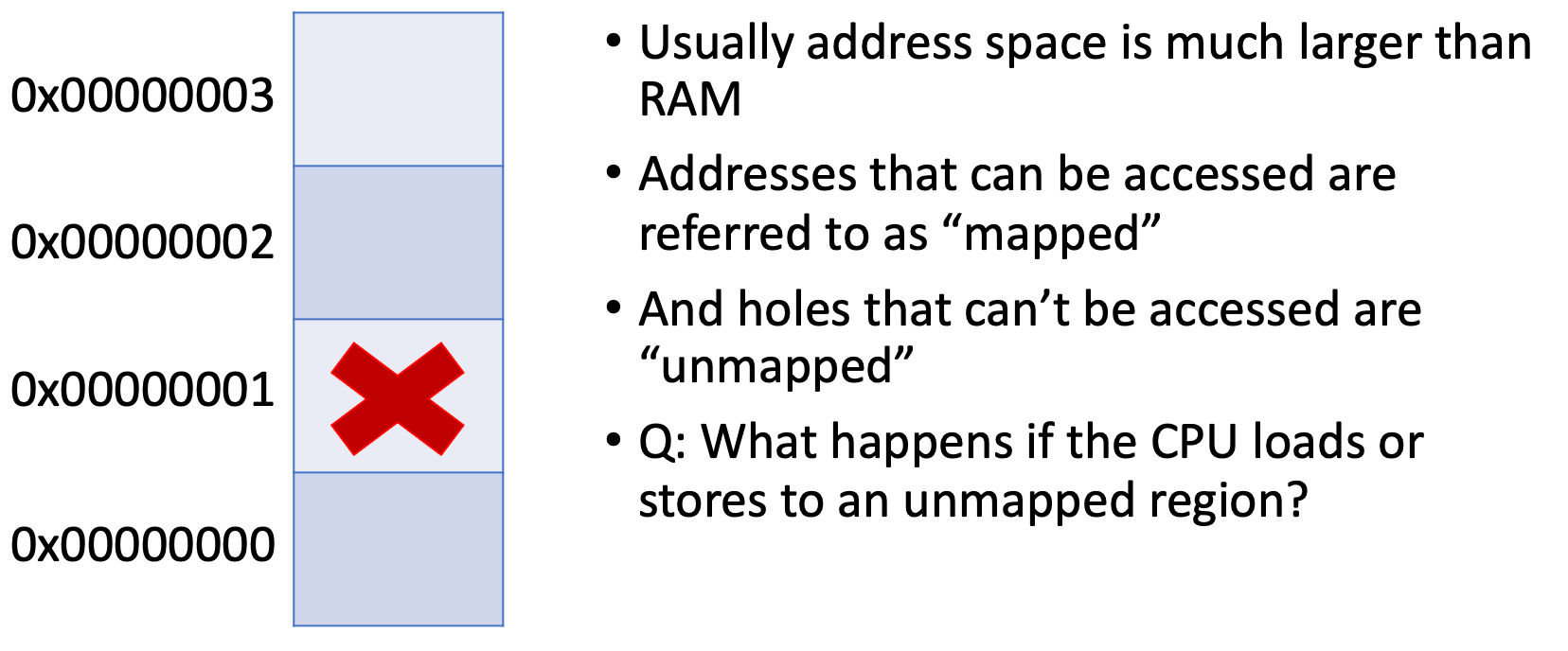

Idea #1: Address spaces can have holes

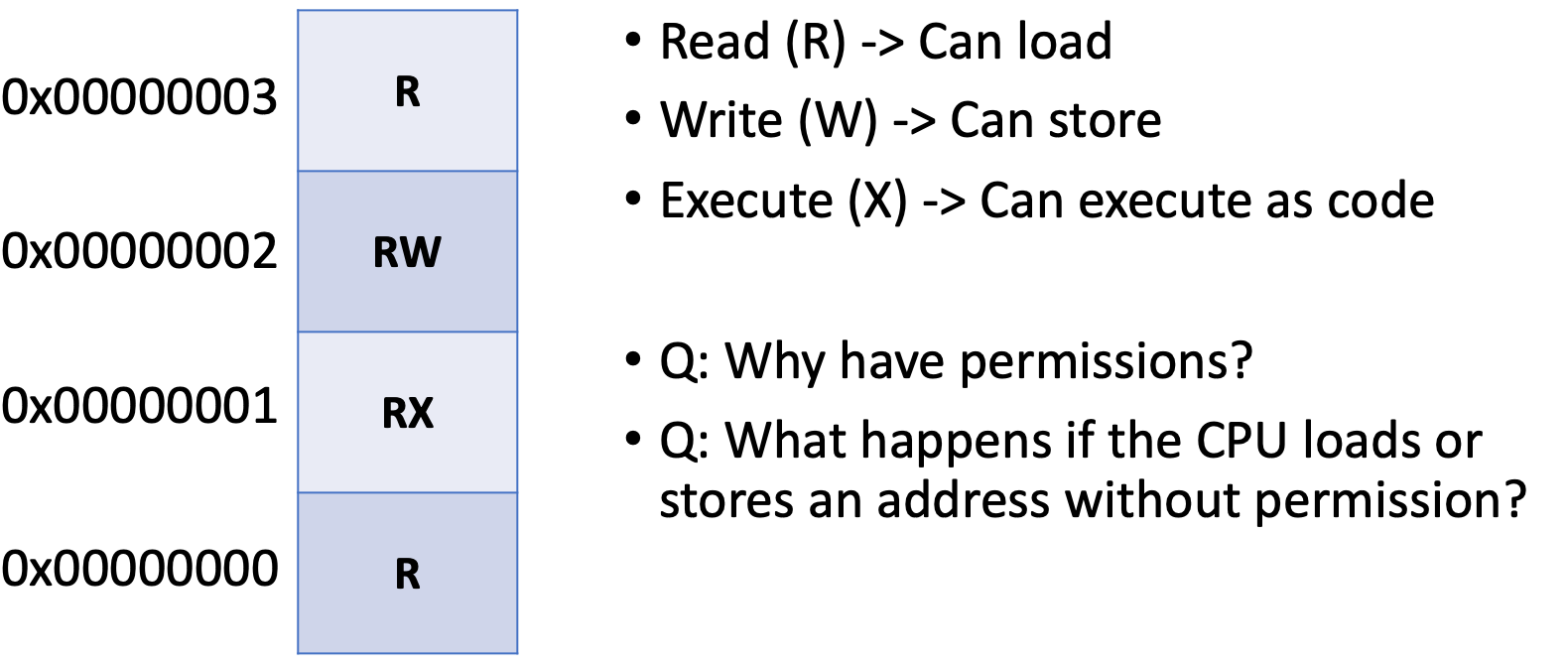

Idea #2: Address spaces can have permissions

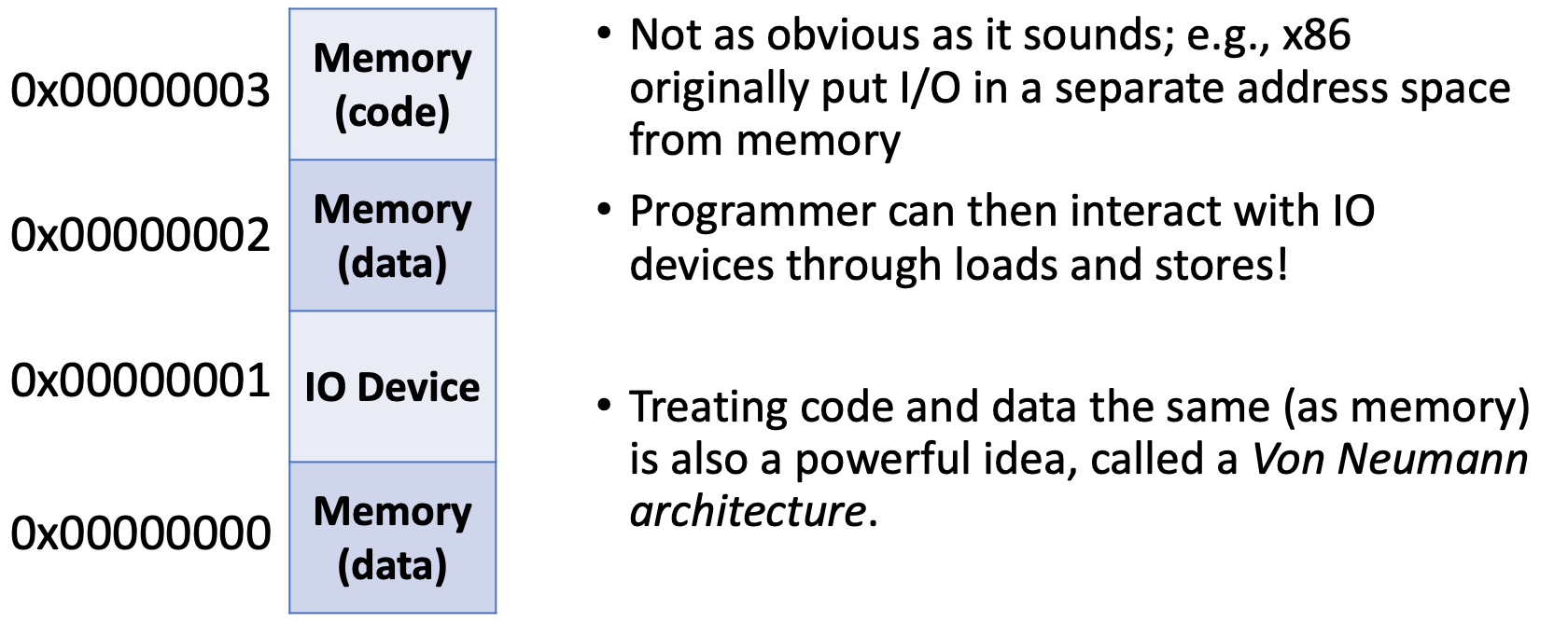

Idea #3: Combine RAM and devices

More ideas not discussed today

Typical granularity for mappings is a page (4KB), not a byte

Idea #4: Virtual memory

Allows each process to have its own address space

Idea #5: Cache coherence and consistency

Allows multiple CPUs to share memory in an address space Will be covered in later lectures.....

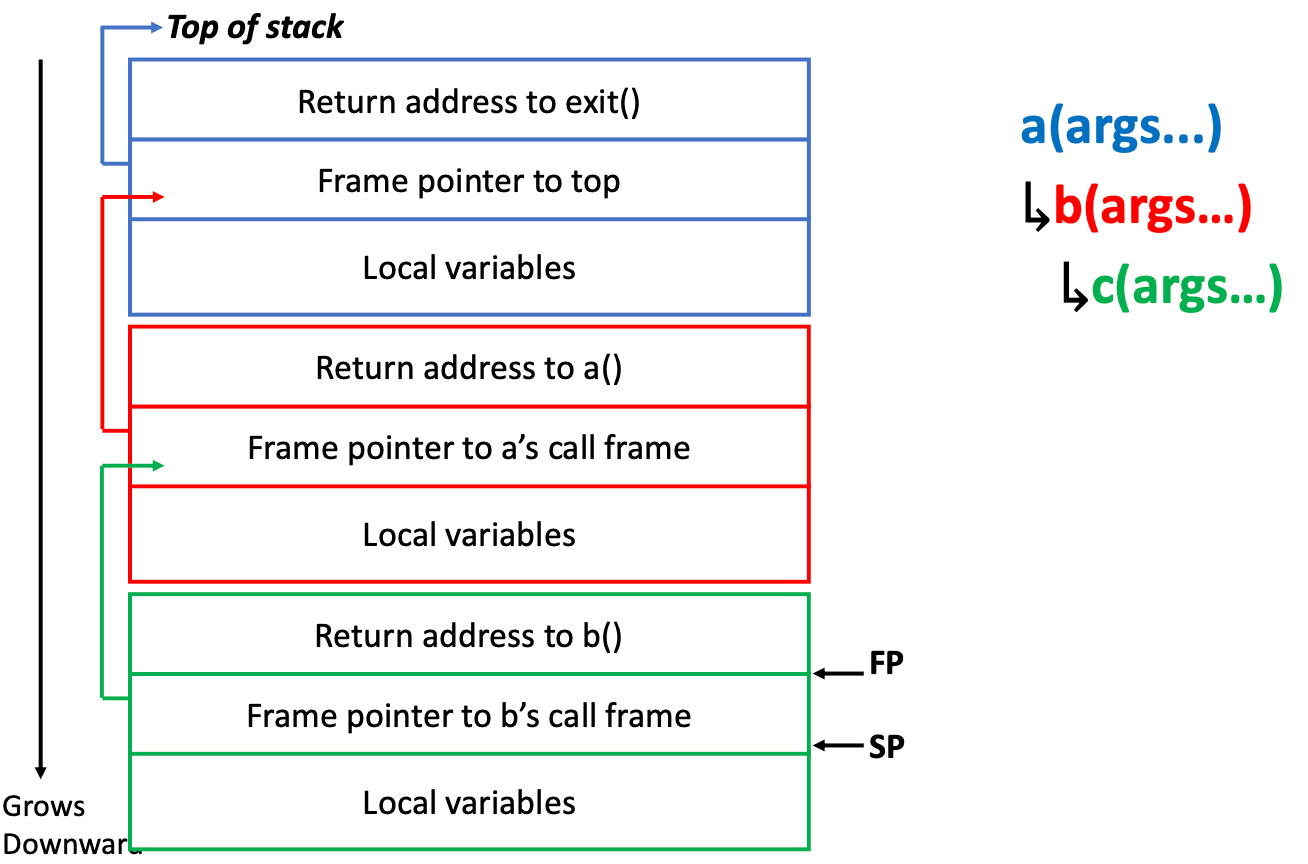

2.1.3 Compiler/Library Layer: Stacks and Heaps¶

memory allocation

1. Stack

A stack allocates memory when a function is called and frees itwhen a function returns.

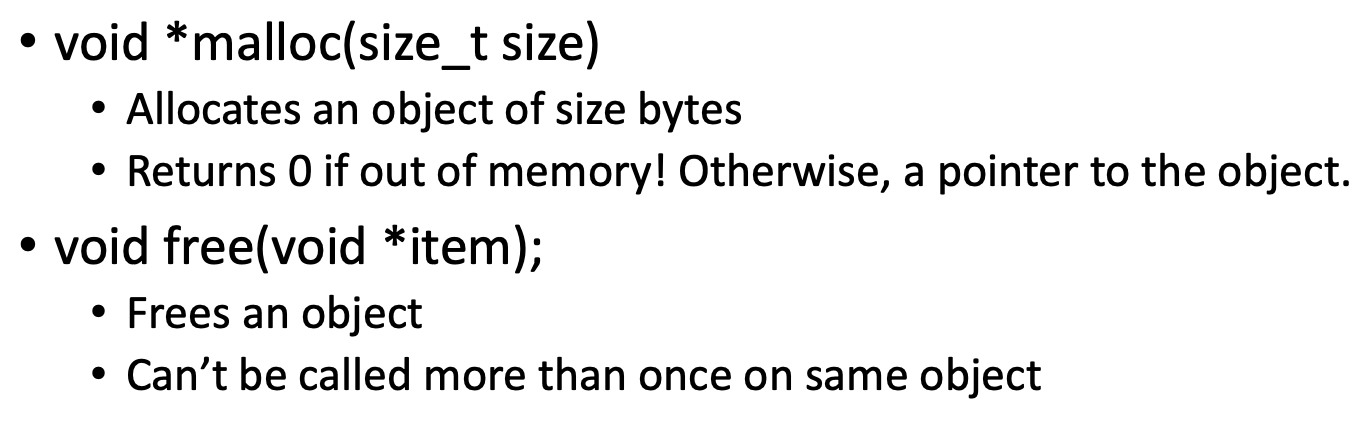

2. Heap

A heap manages memory that is allocated and freed independently of function invocationst.

struct foo *f = malloc(sizeof(*f));

if (!f) // handle out of memory error

memset(f, 0, sizeof(*f)); // initialization

// do something with f

free(f);

3. When is it better to use a stack vs. a heap?

- Always prefer a stack, except if the object must remain valid after the function returns or if the object is too large

- Why? More efficient and simpler

- Note: A stack is generally much smaller than the heap

2.1.4 Common memory management pitfalls¶

- Using memory after freeing it

- Freeing the same object more than once

- Forgetting to initialize memory (nothing is zeroed automatically)

- Writing beyond the end of an array (buffer overflow)

- Forgetting to free an object (memory leak)

- Casting an object to the wrong type

- Forgetting to check if an allocation failed

- Using pointers to locations on the stack (if they could return)

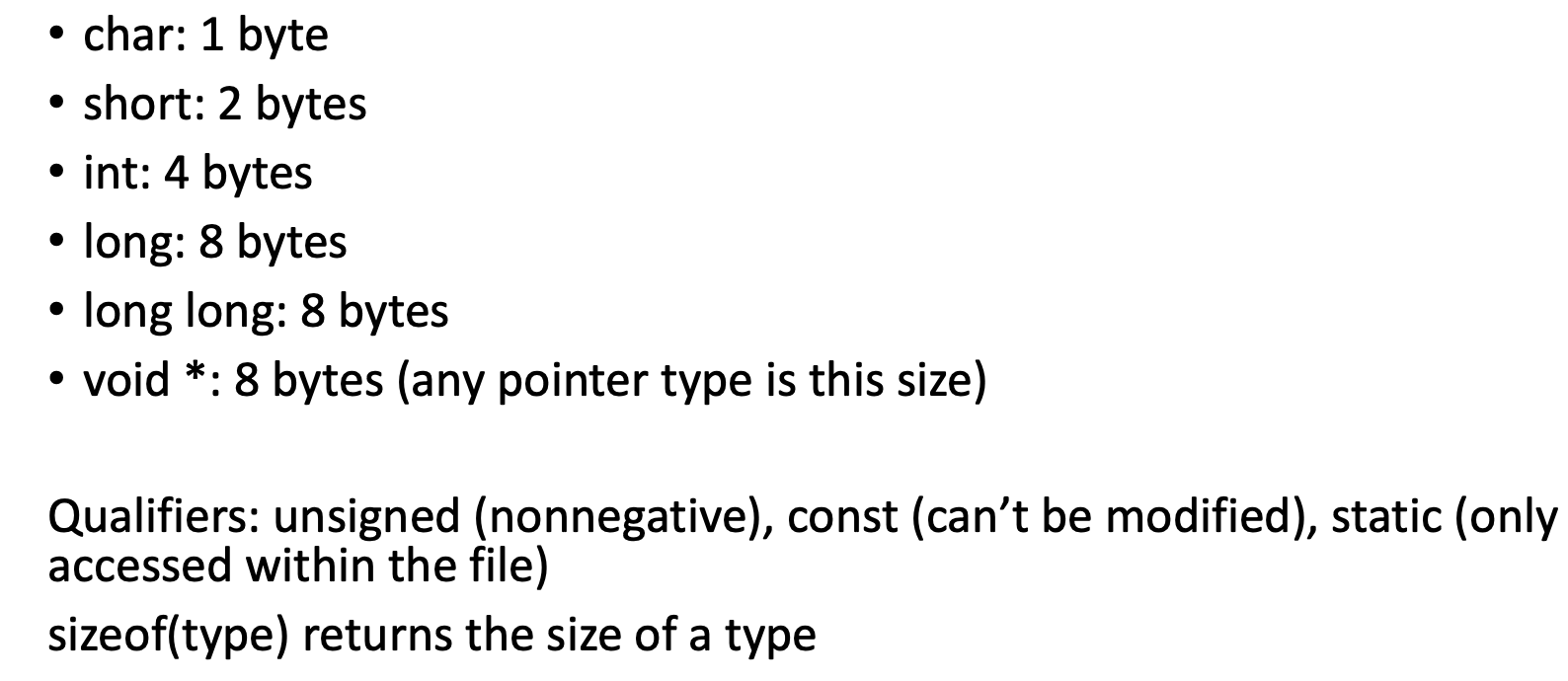

2.2 Why C¶

1. good for low-level programming

- easy mapping between C and RISC-V instructions

- easy mapping between C types and hardware structures

2. minimal runtime

- easy to port to another hardware platform

- direct access to hardware

3. explicit memory management

- no garbage collector

- kernel is in complete control of memory management

4. efficient: compiled (no interpreter)

- compiler compiles C to assembly

5. popular for building kernels, system software, etc.

- good support for C on almost any platform

why not?

- easy to write incorrect code

- easy to write code that has security vulnerabilities

2.3 use of C in xv6¶

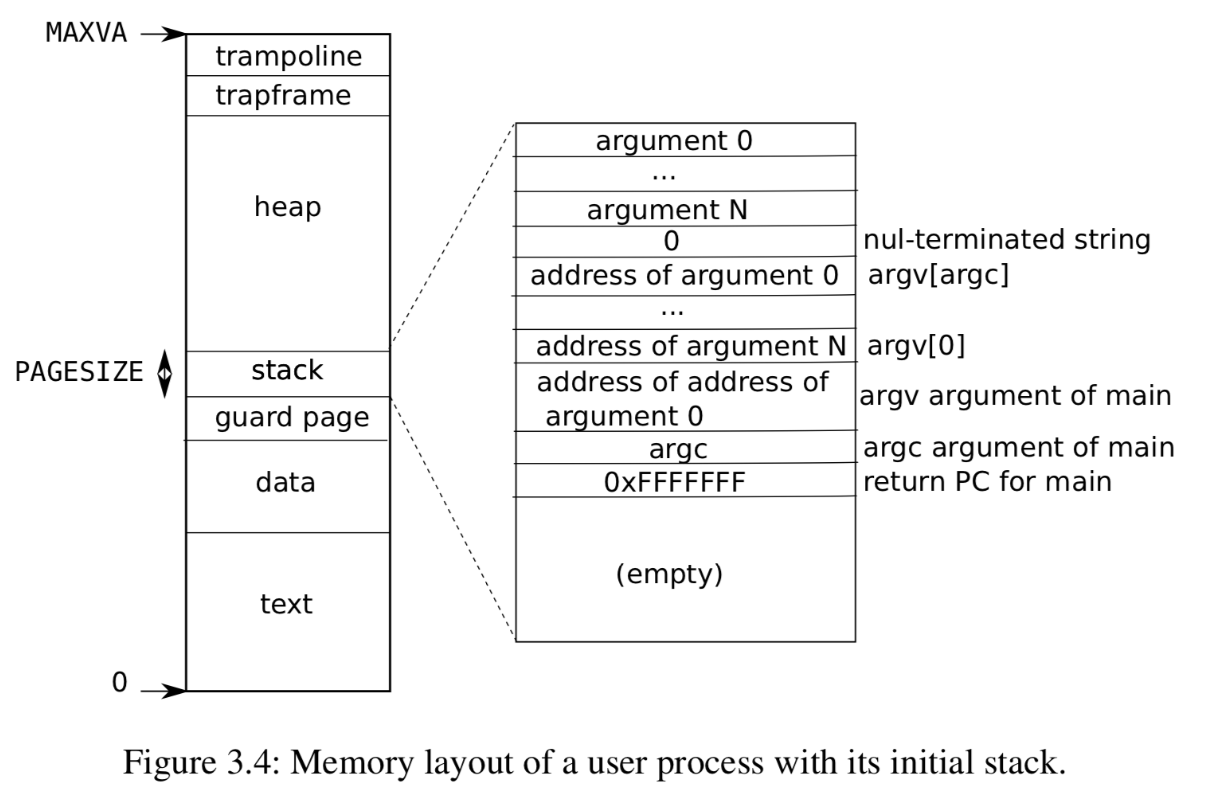

2.3.1 memory layout¶

- text: code, read-only data

- data: global C variables

- stack: function's local variables

- heap: dynamic memory allocation using sbrk, malloc/free

- Makefile defines how

- gcc compiles to .o

- ld links .o files into an executable

- ulibc.o is xv6 minimal C library

- executable has a.out format with sections for:

- text (code), initialized data, symbol table, debug info, and more

- riscv64-linux-gnu-objdump -S user/_cat

- 0x0: cat

- 0x8e: _main

- what is _main?

- defined in ulib.c, which calls main() and exit(0)

- where is data memory?

- in data/bss segment

- must be setup by kernel

2.3.2 pointers¶

- a pointer is a memory address

- every variable has a memory address (i.e., p = &i)

- so each variable can be accessed through its pointer (i.e., *i)

- a pointer can be variable (e.g., int *p)

- a pointer has a memory address, etc.

- pointer arithmetic

- referencing elements of a struct

#include "kernel/types.h"

#include "user/user.h"

int g = 3;

int

main(int ac, char **av)

{

int l = 5; // local variables don't have a default value

int *p, *q;

// take address of variable

p = &g;

q = &l;

printf("p %p q %p\n", p, q);

// assign using pointer

*p = 11;

*q = 13;

printf("g %d l %d\n", g, l);

// struct

struct two {

int a;

int b;

} s;

s.a = 10;

struct two *ptr = &s;

printf("%d %d\n", s.a, ptr->a);

// can take address of any variable

int **pp;

pp = &p; // take address of a pointer variable

printf("pp %p %p %d\n", pp, *pp, **pp);

int (*f)(int, char **);

f = &main; // take address of a function<

printf("main: %p\n", f);

return 0;

}

2.3.3 arrays¶

- contiguous memory holding same data type (char, int, etc.)

- no bound checking, no growing

- two ways to access arrays:

- through index: buf[0], buf[1]

- through pointer: *buf, *(buf+1)

#include "kernel/types.h"

#include "user/user.h"

int a[3] = {1, 2, 3}; // an array of 3 int's

char b[3] = {'a', 'b', 'c'}; // an array of 3 char's

int

main(int ac, char **av)

{

// first element is at index 0

printf("%d\n", a[0]);

a[1] += 1; // use index access

*(a+2) = 5; // pointer access

printf("%d %d\n", a[1], a[2]);

// pointers to array elements

printf("a %p a1 %p a2 %p a2 %p\n", a, a+1, a+2, &a[2]);

// pointer arithmetic uses type

printf("%p %p\n", b, b+1);

return 0;

}

2.3.4 strings¶

- arrays of characters, ending in 0

#include "kernel/types.h"

#include "user/user.h"

char *s = "123";

int

main(int ac, char **av)

{

char s1[4] = {'1', '2', '3', '\0'};

// s and s1 are strings

printf("s %s s1 %s\n", s, s1);

// can use index or pointer access

printf("%c %c\n", s[0], *s);

printf("%c %c\n", s[2], *(s+2));

// read beyond str end; DON'T DO THIS

printf("%x %p %p\n", s1[4], s1, &s1[4]);

// write beyond str end; DON'T DO THIS

s1[4] = 'D';

return 0;

}

- ulib.c has several functions for strings

- strlen() --- use array access

- strcmp() --- use pointer access

2.3.5 lists¶

- single-linked list

- kernel/kalloc.c implements a memory allocator

- keeps a list of free "pages" of memory

- a page is 4096 bytes

- free prepends

- kalloc grabs from front of list

- double-linked list

- kernel/bio.c implements an LRU buffer cache

- brelse() needs to move a buf to the front of the list

- see buf.h:two pointers: prev and next

2.3.6 bitwise operators¶

0b10001 & 0b10000 == 0b10000

0b10001 | 0b10000 == 0b10001

0b10001 ^ 0b10000 == 0b00001

~0b1000 == 0b0111

2.3.7 common C bugs¶

- use after free

- double free

- uninitialized memory

- memory on stack or returned by malloc are not zero

- buffer overflow

- write beyond end of array

- memory leak

- type confusion

- wrong type cast